Have We Gotten Better at Writing Code?

I wanted to find whether the developers working on Linux kernel have gotten better at writing bug-free code. To that end, I analyzed the data about vulnerabilities from Kees dataset fortified with LOC data of various Linux versions when the bug was introduced.

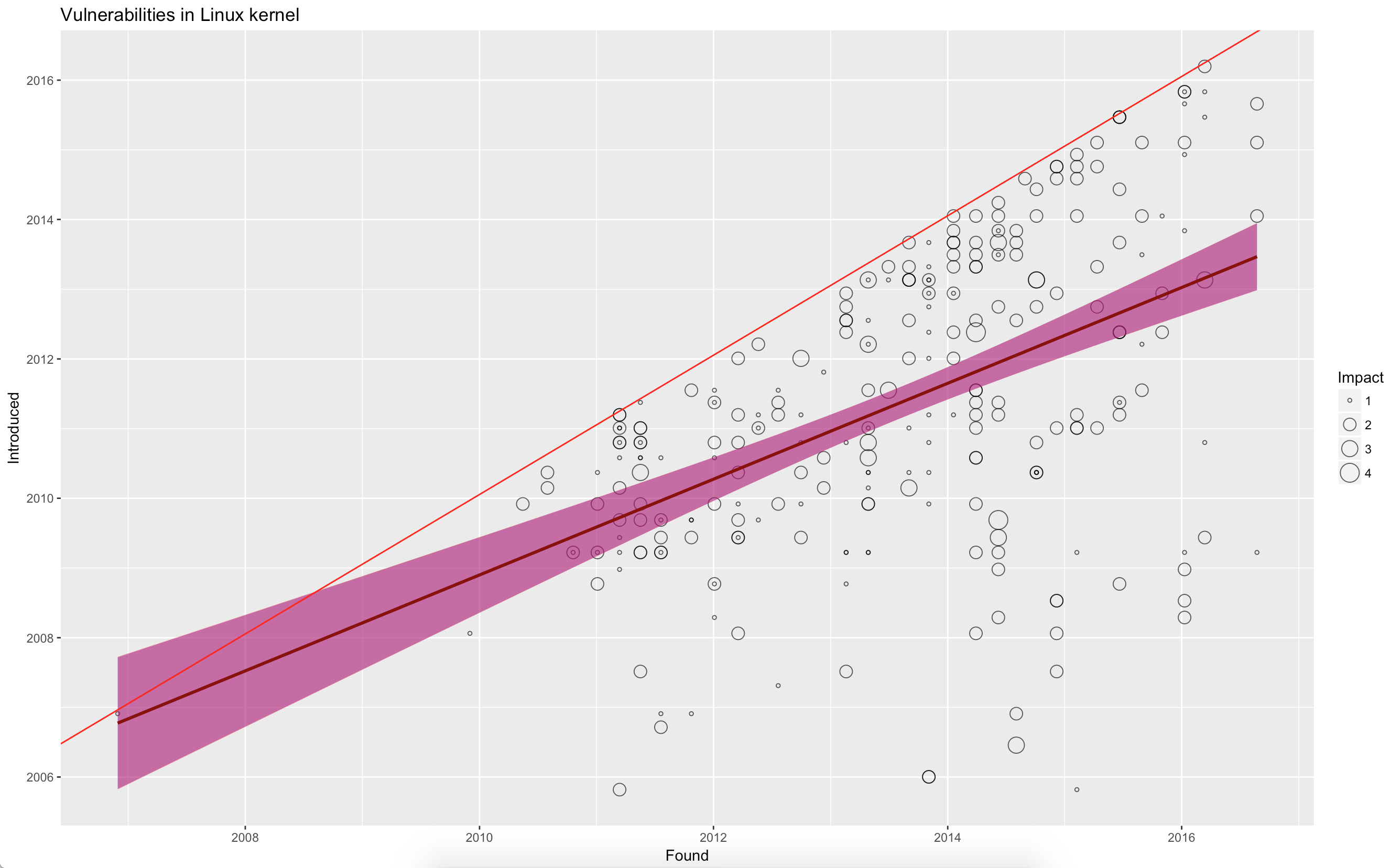

The plot below shows my findings.

In the plot, I have used numbers 4,3,2,1 for critical, high, medium, and low impact vulnerabilities. The X axis represents the date at which a vulnerability was found, and the Y axis represents the date at which it was introduced (this is from Kees dataset, where he analyzed 557 vulnerabilities).

The red line represents same version fixes. That is, the bug was found and fixed in the same version. Assuming the LOC remained stable, if the vulnerabilities were getting fixed in the same rate as it was introduced, we should expect the regression line \(Introduced = \beta_1 \times Found + C\) to be parallel to the red line. However, that regression line is represented by the dark red line. This suggests that developers of Linux kernel have actually become worse at finding and fixing bugs overtime. The regression has an \(R^2 = 0.2564\) which says that our model is not a very strong fit.

But wait. There is more to it. We ignored the impact of LOC. What if the number of bugs is actually related to the size of the code base? Incorporating that into our regression:

\[Introduced = \beta_1 \times Found \times LOC + \beta_2 \times Found + \beta_3 \times LOC + C\]Indeed, the new regression has a high \(R^2 = 0.9893\), which suggests that the divergence is almost completely explained by the change in size of the kernel.

What does this mean? It means that the Linux developers are neither getting better nor getting worse at writing bug free code as the releases go by. Indeed, if we instead look at the regression \(Introduced = \beta_1 \times LOC + C\) we get \(R^2 = 0.9876\), which suggests that just the size of the code base explains most the vulnerabilities we see.

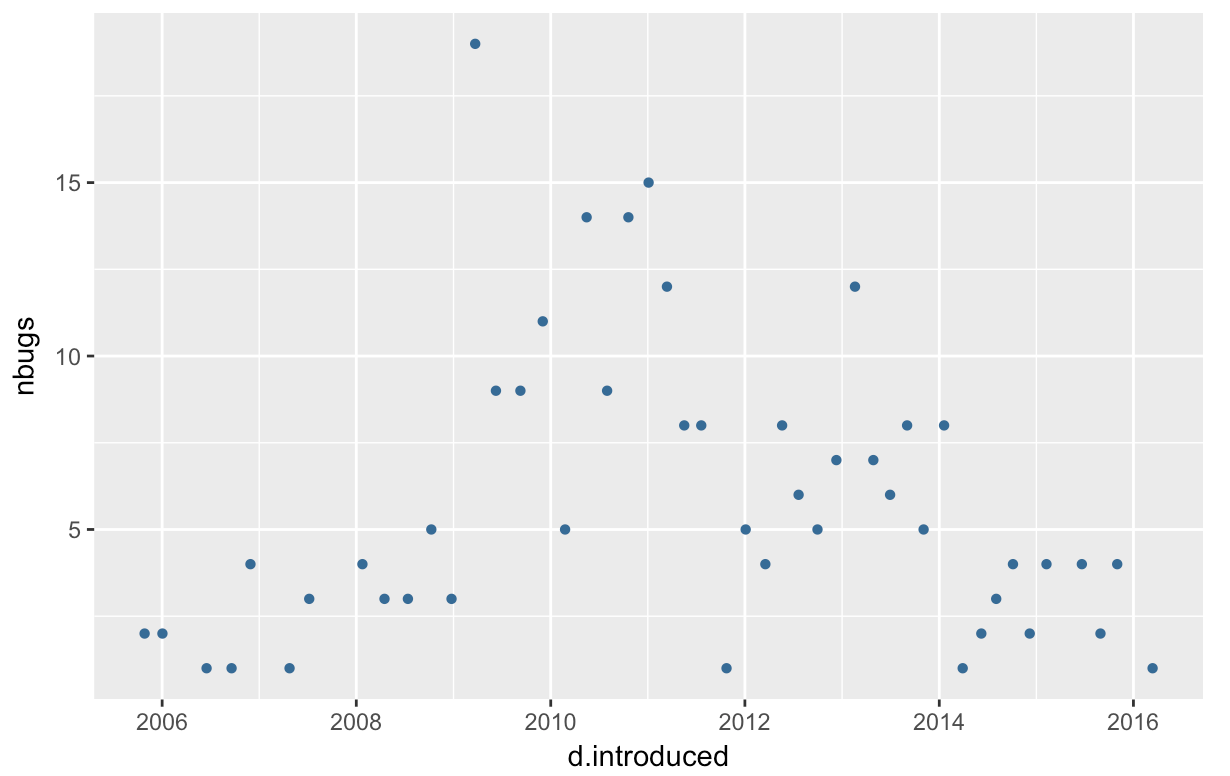

Here is a graph of the number of vulnerabilities introduced in each year.

The interesting thing to note here is that the number of new introduced

vulnerabilities seem to peek at about 2011. Does it mean that the new versions

are much less vulnerable? Probably not. This seems to suggest that a

vulnerability typically requires about 6 years before most of the bugs

(about 95% quantile from the current data) are flushed out.

The interesting thing to note here is that the number of new introduced

vulnerabilities seem to peek at about 2011. Does it mean that the new versions

are much less vulnerable? Probably not. This seems to suggest that a

vulnerability typically requires about 6 years before most of the bugs

(about 95% quantile from the current data) are flushed out.

The source for analysis can be found here and the data can be found here.